Por Glenn O'Brien

Fuente: Art Forum (2002)

http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0268/is_2_41/ai_93213709/

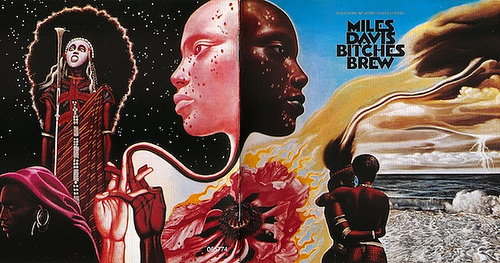

I first encountered Mati Klarwein in 1970. Miles Davis had just released his revolutionary Bitches Brew, which featured Mati's painting on the sleeve. It was a perfect visual synthesis of Miles's magical amalgam of funk, rock, jazz, and psychedelia. Mati soon became a famous artist, quite outside the art-world path, for the lavishly detailed, cosmically erotic paintings that fronted albums by Santana, the Chambers Brothers, Earth, Wind Fire, and others.

I believe that at the time Mati was going by the name Abdul Mati Klarwein. He once said, "If all Jews would add an Arab name to theirs and all Arabs added a Jewish name then the hatred they have for each other could be attenuated considerably."

These days I think a lot about Mati, the Jewish Muslim Sufi Christian who was as close to a Buddha as anyone I've ever met. He saw the arts, especially music, as a healing force, Interestingly, musicians always felt the same way about his work: His paintings have qualities they can't resist--virtuosity, rhythm, and free-associative iconography akin to their modes of improvisation. Jon Hassell, who was one of his closest friends, told me, "I guess the popularity of his work militated against it being perceived as precious, but what does it say about the art world that it was immune to its clear and present beauty?"

Mati Klarwein was born in Germany in 1932. His parents fled Hitler when Mati was two, taking refuge in Palestine. His father, architect Joseph Klarwein, designed the Knesset building in Jerusalem. In 1948, during the war that resulted in the founding of Israel, Mati moved to Paris, first attending the Ecole des Beaux-Arts and later studying with Fernand Leger. As a teen, he zoomed down to Saint-Tropez, where he acquired an eclectic group of friends, including Brigitte Bardot and Ernst Fuchs, the Viennese "fantastic realist" painter who encouraged him to work in casein tempera, a medium he would stick with. From there Mati embarked on a global trot that took him to Tibet, India, Bali, North Africa, Turkey, and across Europe. In 1964 he arrived in New York, where he exhibited a painting that had taken him over two years to make. Titled Crucifixion, 1963-65, it created a scandal and a sensation. The crucified figure was an upside-down black woman whose breasts spouted milk; surrounding her was an ornate tree of life, populated by gods, holy men and women, and tableaux of Kama Sutra-versed nymphs.

The painting was the centerpiece of a huge work, a room comprising seventy-eight panels, that Klarwein called The Aleph Sanctuary, 1971. In the early '70s, I saw the sanctuary complete and was transported by these dreamy, fantastic paintings. By then, Mati was considered the premiere psychedelic artist. He was really just a painter who loved the Renaissance, Surrealism, and the Indian Tantric school. His "psychedelic" style predated his knowledge of psychedelics. He didn't paint on drugs, although in order to be included in the influential Grove Press book Psychedelic Art he told the authors that he got ideas for paintings on drugs. He liked to quote his friend Dali: "I don't take drugs. I am drugs."

Women, music, and nature were undoubtedly greater catalysts for Mati's vision than the alkaloids he occasionally ingested. (I believe his drug of choice was Fernet-Branca, a digestif.) Today he is sometimes called an "outsider" artist. Since he was Leger's prize student, Dali's friend, and Warhol's "favorite painter," the tag is a little strange, but the fact that his fame came from the popular medium of album art and not through "proper" channels seems to have doomed him to the art world's labels of derision: outsider and illustrator.

Mati did make "bad" paintings. His good paintings were so detailed, despite their small scale (his largest was about seventy by seventy inches), that they took years to finish, and so he supplemented his income while amusing himself by making what he called "Improved Paintings." He bought flea-market canvases and embellished them in the style of the original artist. This body of work didn't win the art world's heart either, although it showed off his masterful sense of humor and virtuosity. When Julian Schnabel buys a thrift-shop painting and remakes it the size of Guernica, it's still a bad painting, just a big bad painting. Mati made them better, and that seems emblematic of his approach to life. He left the world a far more beautiful place than he'd found it.

Mati Klarwein, the great "commercial" artist, passed on in March, a couple of months after Absolut reproduced a detail of his painting for Bitches Brew with the caption "Absolut Miles." Miles would probably have been pissed, since he was a painter too, but I'm sure Mati had a good laugh, although he preferred Fernet-Branca to vodka.

Glenn O'Brien is a writer who lives in New York.

This article is © Copyright 2002 Artforum International Magazine, Inc. Gale Group