By Rob Young

Source: The Wire (1998)

http://www.jonhassell.com/mati.html

The great visionary painter Mati Klarwein died in March 2002, aged 70. Several of his paintings adorn Jon Hassell's record sleeves: Earthquake Island, Dream Theory in Malaya, Aka-Darbari-Java and Maarifa Street. From Salvador Dali to Miles Davis, from Jimi Hendrix to Jon Hassell and beyond, artist Mati Klarwein makes the connections between surrealism, African-Americanism, hippydom and the Fourth World.

IN 1960, AN artist called Abdul Mati sent a copy of a portrait he had made of jazz saxophonist Yusef Lateef to the musician himself. Lateef, a Muslim, liked the painting—Lateef's bald pate almost swamped by a sea of encroaching flora—and sensed a kinship: he wrote back with a salutation to his "Dear Bro", and offers of record sleeves in the future. Abdul Mati approached Lateef one evening after a gig at New York's Five Spot, but when Lateef saw that this 'Abdul' was white, he turned away without a word.

Abdul Mati didn't let this trouble him unduly. Mati Klarwein—the name he reverted to after this incident, and which was given him by his German parents—has always been acutely sensitive to the age-old standoffs between black and white, Muslim and Christian, science and art, nature and technology. "My experience with Yusef Lateef was not 'unfortunate', as you say," he says, in philosophical mode, at his home in Mallorca. "It was very indicative of the time when 'black' had to become 'beautiful'—because it was!—and had to find its own identity and cautiously dig into its African past for that purpose. Going back to the animistic true past was too much of a jump, so they settled for Islam, being another facet of monotheism, and a provocative contrast to the Gothic Christianity that was and is still oppressively segregating them with its smug self-righteous patronising attitude."

Klarwein is prone to such outbursts (try these: "The Sistine Chapel is a pompous comic book and Yves Klein is a vulgar illustrator of Zen Buddhism"; or "Talking about drugs can be as interesting as talking about sex, depends who does the talking—William Burroughs or Nancy Reagan"), but his opinions are informed by a life of travel—not tourism, but a far deeper immersion in foreign cultures and belief systems—that has given him a wider perspective on the ideological tensions that keep the late 20th century global dynamic on the rack. His paintings since the Lateef episode are radiant with such oppositions, spangled with symbols, sex and sunlight, and refracted and intensified through the tinted shades of LSD. In fact, for an explanation of the 'Fourth World' concept furthered by Jon Hassell, Klarwein's pictures offer precise visual analogues for this conceptual dreamtime, in which ancient-to-future sounds and images converge and mutate, creating a surreal new estate founded on the eternal circling of information and cultures around the globe. As Klarwein writes: "I'll never forget the expression of the Sayonara indians from the Amazon basin when they were listening to us play the Fifth Brandenburg Concerto in B flat by JS Bachofen on the Jew's harp made from wishbones extracted from whales' clitorises while we waited for Duchamp's bicycle wheel to be repaired at the workshop of the Beijing People's Museum of the repetitious, repetitious, repet..." It doesn't get much more Fourth World than that.

MATTHIAS KLARWEIN was born in 1932 in Hamburg, Germany; the story of how he became the counterculture's artist-in-residence is due in part to the rise of Nazism. On Hitler's accession to power, his Jewish parents fled with Mati to Palestine. An early ambition to direct movies in Hollywood came to nothing, and instead he travelled to Paris to study under the French painter Fernand Leger. Naturally, France introduced him to the artistic and showbiz milieu that was shaping up in the capital and on the Riviera. One of his most influential meetings was with Salvador Dali: "I read Dali's Private Life Of Salvador Dali when I was 20 years old," he says, "and I have never been the same person since. I met him at the age of 30 for the first time, and we saw each other regularly in New York and Paris during the 60s and early 70s. He was my spiritual father, and some even thought I was his illegitimate son. We were also each other's pimps and cultural spies." Dali's decadent years as both king and court jester to rock stars, models and assorted hippy loons have been well documented by those who were either there at the time or wish they had been, "(Dali) hated music," is Mati's version of events. "He hung out with rock stars because of their fame and/or genius. He believed that there are three things that cretinize us humans: love, children and music. Just look at my life and you'll see that the proof is in the pudding."

As a young man, Mati became the travelling companion of an unnamed but wealthy woman with whom, as he rather grandly puts it, "I didn't leave one stone unturned; every electron that I ran into changed my life production drastically". It was perhaps during these nomadic years, passing through Tibet, India, Bali, North Africa, Turkey, Europe and the Americas, that he became saturated with the different landscapes, both inner and outer, that twist and writhe over his canvases. Once he had fetched up in New York's art scene in the early 60s, he began synthesising all these impressions into his distinctive, huge tantric paintings, aided by the surrounding climate. "Of course Sun Ra was part of it, and so was 'droogs', as Dali would call them. One of the achievements of the 60s spirit, besides ecological awareness, was the elimination of the 'either-or' mentality, and the birth of rhizomatic reasoning as postulated by Deleuze, Castaneda and Leary. And the battle isn't over yet!"

No wonder, then, that at the end of the 60s Miles Davis seized on Klarwein to illustrate the sleeves for the albums he recorded to burst out of the chrysalis of jazz into the electronic age: Bitches Brew and Live-Evil. His memories of the crowded and artistic circles of New York in which he met Miles are similarly hazy. "I hooked up with Miles the way I hooked up with everything else in life: through the women I've known. be they friends or lovers, they are all mothers with excellent taste. Without them I'd be a dead spermatozoid in a dry puddle, and Miles saw that in my paintings. The only time he discussed subject matter was for Live-Evil. He asked me to paint a toad for the 'Evil' side. So I painted J Edgar Hoover as a toad in drag—which turned out to be another one of my prophetic insights."

At this time, he also counted Jimi Hendrix and Timothy Leary among his close friends, and even painted a record cover for the semi-mythical, unfinished Hendrix collaboration with Gil Evans. A sleeve for Zonked, a vocal album by Miles's then wife Betty Davis, was shelved after Miles discovered she had been sleeping with Hendrix. Meanwhile, the original painting from Bitches Brew remains lost: sold to an unknown buyer, although Klarwein claims he's not troubled by the loss of an original—the important thing is the image itself.

Klarwein's pictures re-ignite dialogue between ancient tribal history and contemporary civilisation. Paintings such as 1964's 'Crucifixion (Freedom Of Expression)', whose multiracial orgies on a backdrop of holy sites and lush jungles caused 'outrage' (as paintings seem to do) when exhibited in New York. You can almost read them like one of Cheikh Anta Diop's histories of Africa as the cradle of civilisation. In Klarwein's world, culture is a perpetual-motion machine where hierarchies are overturned and history collapses into itself, tunnels open up through the Earth allowing cultures, creeds and symbols to project themselves on each other's irises, male and female. Forms are melted through sex into a hermaphroditic anthropomorph. "As far as my own 'cultural difference' is concerned," he says, "I considered myself very lucky to have had the chance to grow up in Palestine-Israel, a land where you can walk 2000 years back in history by merely strolling down to the end of the street you live on, especially in Jerusalem. How shallow American pop music sounds compared to the chanting of Oum Kalthoum or a raga by Ameer Khan! And where would rock 'n' roll be without the pure African energy channeled over by the slave ships? The American Indians were much too proud to become anyone's slave, much too 'spaced out'. They were like us: children of the cold weather too. Life for them was not a permanent party like it is for the Africans."

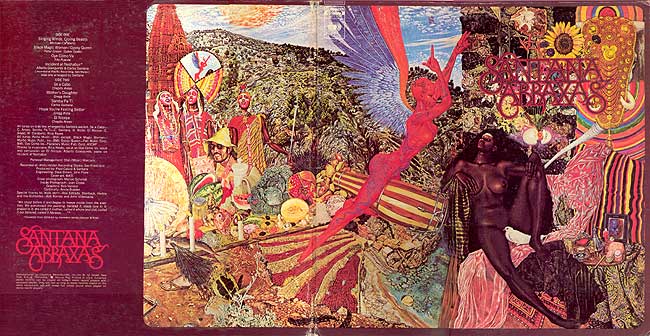

Nevertheless, on account of his work for Miles, Hendrix and Carlos Santana (the guitarist discovered Klarwein's painting 'Annunciation' in the Aleph Sanctuary, a small chapel in Mallorca, and used it for his Abraxas LP), Klarwein has become inextricably associated with astro-black chic. "The astro-black culture was part of the cultural process black and white America needed in order to free itself from spiritual oppression," he explains. "The esoteric and cosmic consciousness is a powerful antidote to the crass mainstream consumerism that is drowning us all, where God is just a number, any number. Esoterics pulled us through the terrible nuclear holocaust paranoia of the 50s—engendered by the traumatic battle against square-moustache totalitarianism of the 40s, caused by the blind faith we had in the machines in the 20s and 30s ... all the way back to Adumb and Evil."

Things change. By 1976, the fire of that era was reduced to embers. Hendrix was long dead, Miles had hung up his horn; Herbie Hancock was setting the scene for Electrofunk. Mati met Jon Hassell, whose own experiments with atmosphere, trumpet manipulation and textural freeplay was beginning to water the bleached deserts left by the battlescapes of cosmic jazz. "I know Jon since 1976 when I moved to SoHo and into the 'fine art' world of Lower Manhattan—before that it was just sex 'n' drugs," says Mati. "The mind took over. The synthesizing, of past experiences into something globally significant, the sublimation of our erotic and exotic fantasies into an awareness of other cultures, and our indulging into sampling them and experiencing of new outlets of expression by integrating these cultural samples in our art. This we had in common and enjoyed sharing."

The art that Mati produced for Hassell's Fourth World LPs, released on Brian Eno's Ambient label, was different: pure landscapes, jet's eye views of transfigured tracts of land. He calls these 'Real Estate' paintings, or 'Inscapes'. 'Soundscape', which illustrates Hassell's Aka-Darbari-Java, is a prime example of the way the paintings function as landscapes and maps simultaneously: nature carved up and reshaped by economic and social forces. "Your definition is brilliant," he says. "I should have called them 'Mapscapes' instead of 'Inscapes'. Also, the paradoxical fact of man's manipulation of nature can make it either a more fascinating and uplifting an experience, like the rice terraces of Indonesia, or a tragic and depressing one like the landscape of strip-mining. A lonely Chinese wall stretching for miles across a landscape can do marvels for the mind, and also for the purely abstract compositional requirements of the painting itself. Again, the balance between the concepts and emotion is the issue. The 60s were emotional times, the 70s returned to the conceptual, in music too, from rock 'n' roll to New Wave. From Beatles to Talking Heads—insects with brains

"Personally," he continues, "I prefer the 70s for music than the mushy nostalgic 60s, with its Art Nouveau conventionalism. One thing I could never figure out is why all the best pop music always comes from England. It must be the developed sense of humour has a lot to do with it. America hasn't suffered enough yet."

Paralleling Hassell's refinement of sampling aesthetics, Mati's subsequent work has incorporated a healthy dose of cultural theft in his series of 'improved paintings'. Typically, he will buy existing paintings and work over them with his own brush, executing a kind of visual 'remix'. "The urge to improve paintings started with me in the early 60s and I have done a good hundred since then," he explains. "Sampling or appropriating are just hip euphemisms for stealing and robbing. In the US, they would be illegal. They are not 'sampling', nor are they 'appropriations': they are 'improved' paintings—I buy them in flea markets for not more than and proceed to improve them, remaining as much as possible within the style of the original painter. I leave the signature, if there is one, and add mine to it. It's all upfront. The only secret is: who painted what? And that is the main concept: individuals are an illusion, or elusion, only concepts are real. It's not your organ, honey, it's the way you grind."

Klarwein has published several books of his writings over the years, and it's a medium he increasingly enjoys: "A picture might be worth a thousand words but a good sentence is worth a thousand windows," he says. A Thousand Windows is, inevitably, the title of his latest book of images and text (published on his own Max Publishing imprint), and readings from it have appeared on No Man's Land, a CD released during 1997 featuring music by Swedish percussionist/composer Per Tjernberg. The two have been friends for some time—Mati contributed cover art on three previous albums by Tjernberg, who has worked with Don Cherry, Dr John and Okay Temiz. On No Man's Land, he and engineer/sound designer Tom Hofwander create weightless carpets and trailing fronds of sound with berimbaus, Chinese gongs, scraped metal, bird whistles, log drums, clay pots and a full Brazilian batucada, while Mati's lived-in voice recites flamboyant, embellished anecdotes, observations and ruminations on the cosmos. Meanwhile, he's been working on new images for projection during Jon Hassell's live performances, and admits he never turns down any commission. "Life is not a holiday camp," he says. "I don't believe in comfort. Right now I'm painting a shopping centre and I am sweating blood, but it's an offer I can't refuse. Creativity has no limits. Besides, the battle between the mind and the heart still goes on, on both sides of the River Jordan."

No Man's Land by Mati Klarwein and Per Tjernberg was released on Rub-A-Dub Records (RUBCD 15)